I earn commissions from my affiliated links. Please see my disclosure policy for more details.

This post provides a Montessori Language curriculum overview. As you likely know, language development permeates every area of the Montessori learning environment.

Whether you’re looking for Montessori language activities for toddlers, Montessori language activities for preschoolers, or Montessori activities for kindergarteners, you’re in the right place.

Montessori Language Philosophy

Maria Montessori believed strongly (and scientific research backs up this belief) that a child is born with what he needs to develop language. With that said, there are many ways adults can enrich a young child’s language development, especially by preparing the environment ripe for language learning.

At the very least, we know 100% that children will learn to speak as long as they are exposed to some language early in their development.

Reading and writing, on the other hand, need to be taught to the child. A child will learn the words that he is offered through his environment. {Enters the adult.} We control the environment.

It is vital that as Montessori parents and teachers we curate and prepare the child’s environment for language development. In other words, to make this environment rich and full of language learning opportunities.

We know that early in life, a child absorbs language with little effort. He creates an internal understanding of his environment. He must practice using these words during this time. We can help by repeating words, speaking clearly, and using words, especially new words, in complete sentences.

Development of Language

Dr. Maria Montessori is well known for the phrase: “the absorbent mind.” Language acquisition embodies this idea. She wrote extensively on how children absorb their environments and subsequently shape their brains unconsciously – mapping language patterns simply by listening to us talk – during the first three years of life.

Silvana Montanaro supports this idea, “From the moment of birth, infants know that spoken language comes from the mouth, and if we allow them the time, we will notice that when we talk to them, they try to move their mouths similarly.” Even the most recent research supports Montessori’s ideas:

“Studies show that children’s brains code information they see and hear from the earliest ages. This happens automatically.”

Thus, the information available to a child within his environment significantly impacts language development. As a child grows older, he consciously leans into his environment to build on the information absorbed earlier in life.

This stage is precisely the goal of the Montessori environment. Adults facilitate learning by creating an environment ripe for conscious learning, as the adult can do for the unconscious stage. Still, he must allow the child to discover his language.

As Vygotsky and others have theorized, learning a language is a socially based activity. Furthermore, children learn language via interactions with the people in their lives. Children are motivated and better understand writing when it is a meaningful part of their social context.

Dr. Montessori too, believed language learning is driven by a child’s social environment, including interaction with peers and adults. Thus, the environment played a huge part in her approach to language at home and at school.

“The child must create his interior life before he can express anything; he must take spontaneously from the external world constructive material in order to ‘compose’; he must exercise his intelligence fully before he can be ready to find the logical connection between things. We ought to offer the child that which is necessary for his internal life and leave him free to produce.” ~ Dr. Maria Montessori

Other prominent theories on language development exist in literature. For example, Noam Chomsky’s nativist approach theorized that language was driven by an innate structure present at birth. He did not give much weight to the environmental impact.

One main factor supporting his theory is that children learn to read independently and don’t need a “trigger” to acquire language. The brain leads them to speak, for example.

He agreed that a child could develop language more quickly with the guidance of an adult, but even if that adult was not present, the child would learn to speak eventually.

More recently, Dr. Lise Eliot asserts that while language acquisition is largely hard-wired in the brain, learning a language requires social learning and engagement with adults. An environment’s richness will determine the strengthening or deterioration of connections babies generate early in life or simply have at birth.

Indeed, language is a means of interacting with others and begins naturally, yet, the environment must be rich for a child’s optimal development.

The Montessori Environment

The Montessori classroom prepares the child for literacy in two main ways: a well-prepared environment and the teacher’s guidance. Dr. Montessori believed in a well-prepared environment with broad parameters. This point leads to the next critical factor: giving the child the freedom to develop at his own pace:

“Allowed to trust their ears and judgments, many children show amazing facility as they begin to develop language.”

E.M. Standing described the reasons why allowing a child to direct his learning is so critical:

“We have always to remember that our purpose is not to teach grammar but to help the child develop his language.”

Materials in the classroom enable the child to lead his learning beginning in Practical Life. A child learns not only the fine motor requirements for pouring but develops focus and confidence as he learns to care for himself and the environment.

So, the child feels love for his environment. He wants to care for it and to explore the environment even further.

Practical Life leads the child nicely into the Sensorial area, where he can explore more deeply. Materials within the Sensory area give the child more words to describe his world. The ability to speak about his experiences is the primary driver in igniting a child’s desire to learn:

“A supportive environment is one in which children feel empowered to write for real reasons.”

Language permeates all areas of the classroom environment. The environment must support even the earliest attempts to write, whether play dough, pin punching, knobbed cylinders, metal insets, or tracing words. Furthermore, a classroom should not have one “writing center” but multiple “writing centers.”

This approach allows a child to practice writing as he guides himself through the classroom. Additional examples include using nomenclature cards, labeling, tracing, and creating booklets on botany, zoology, geography, history, and even math.

Language materials, specifically, give the child the space to discover reading and writing at his own pace:

“He ought to be directing his activities and making the decisions, not you.”

Materials isolate parts of the shape of the letter and parts of the word (the sounds) so a child can come to write letters and reading on his own.

“What’s important at this early stage is that he gets practice in thinking about how words really sound, gets practice in representing sounds accurately according to the knowledge of letter names and sounds he has available at the time he is writing…far better to let him trust his own accurate judgments and progress according to them than to impose any arbitrariness that at this point who only interfere.”~ Carol Chomsky

Montessori Language Materials

The purpose of the language materials is to give children ways to describe and interact with their environment:

“Learning new words allows children to accurately label objects and people, learn new concepts, and communicate with others.”

Language is a method of communication for the child to express himself and, if the adult allows, to discover the language. As Dr. Montessori writes in The Secret of Childhood,

“The task is essential to arouse such an interest that it engages the whole personality. Let the child discover Writing and Reading, rather than be taught to read and write, they become life-long readers.”

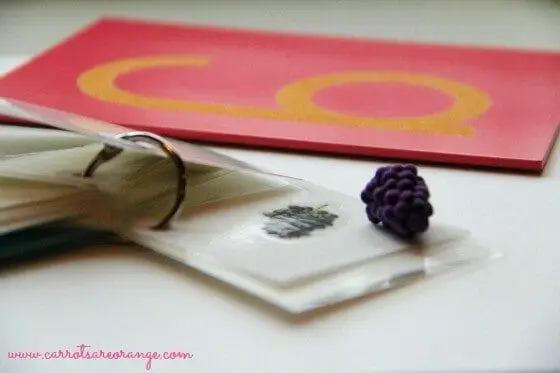

Montessori classrooms utilize a phonetic approach. Furthermore, Dr. Montessori believed learning a language was a holistic developmental process involving the mind and the hand, using sensory development as a driver, at least initially, in a child’s language learning:

“It is combining these two things, then looking at the letter and the touching of it – that is in combining the visual and muscular impressions – that the letter is learned.”

As a child traces a sandpaper letter, for example, he sounds out or hears an adult sound out the letter. Even within Practical Life, as he pours rice from one small pitcher to another, he hears the sound.

“Tracing the letter, in the fashion of writing, begins the muscular education which prepares for writing…touching the letter and looking at them simultaneously, fixes the image more quickly through the co-operation of the senses. Later, the two facts separate; looking becomes reading; touching becomes writing.”

Adults should not stop with materials already prepared for the classroom, however. There are several ways to extend a child’s learning with activities that play with sounds, such as “I Spy” and reading aloud recommended books for isolating different sounds. Adults also can speak robustly to a child.

For example, when a child observes, “There is a bird out the window,” the adult might say, “Yes, I see the Robin perched on the Maple tree outside the classroom window.” Adding context around the child’s observation and interest helps him to learn a language. Supplementing learning with songs and poems that play with sound is also quite effective.

Limitations may include practical control of error when the work involves spelling for example. Since we adults don’t correct the child when he misspells, especially if he is phonetically accurate, we have to wait for the development milestone to appear.

He will spell “cat” correctly but at his own pace. We must have faith in that process. This idea is a difficult one for even the most effective educators, and especially for parents, to embrace as children begin the language development journey.

Language Sequence of Materials

The sequence of materials follows a pattern as the child moves through pre-reading (e.g. matching, sequencing, categorizing, what does not belong?, etc.) to pink (three-letter short vowel words), blue (consonant blends and consonant phonograms) to green (phonemes likes like “ou” and ”ea” are introduced along with long vowel sounds like “bike”) series to grammar (which a child may reach until elementary).

Patterns include moving hands from left to right and in the direction of the proper way to write a “c”, for example. The approach starts in Practical Life and extends into every other classroom area.

Language materials move from concrete to abstract, objects to pictures, sandpaper letters to moveable alphabet, tracing to writing, nomenclature cards, and emphasis of the three-period lesson. Writing is introduced first to the child within the areas of Practical Life and Sensorial.

Dr. Montessori viewed writing as direct preparation for reading.

Montessori’s 3-Period-Lesson

The three-period lesson is beneficial during this time.

- Point to the object, say the name of the object: “This is a pencil.”

- Then ask the child: “Show me the pencil.”

- Then point to the object and ask the child: “What is this?”

Common Misunderstanding of Parents and Teachers

The biggest misconception is that a child should be reading and writing by a certain age. Some adults fail to embrace the range of development across typically developing children. Reading earlier is not necessarily good if that reading is forced, memorized, and generally uninteresting to the child.

Perhaps she will learn earlier than her development would warrant, but one thing is for certain: she will not be a lifelong lover of reading and writing. Furthermore, her communication skills may suffer as a result of the pressure and the approach taken to learning a language.

“Children vary in their language development during these first years, so parents should allow for some variation in children’s abilities at different ages.

They should encourage language development, be patient and seek assistance from a qualified professional if concerns arise about a child’s progress in this area.”

Related Read: What are Montessori Sensitive Periods of Child Development?

Therefore, the more educators can facilitate learning at home or educate the adults in the child’s life with ways they can assist in the child’s learning, especially language, is key.

Provide brief articles written on topics of interest, suggest ways to supplement at home with a list of books, songs, or poems for learning sounds, or teach the parents the all-powerful three-period lesson.

Often parents are looking for ways to supplement their child’s learning but don’t have the information or education they need to do so effectively.

As phonetic awareness enters the arena of development a child begins to understand that different letters and letter combinations have different sounds. At this point the child is no longer absorbing effortlessly, he must begin to organize what he has absorbed during the first three years. The alphabet is one example of how a child organizes this learning.

Adults can help with songs, rhymes, and poems, by tracking the words and sentences as we read books to him, playing I-Spy with letters and sounds, and encouraging the child to sound out words by himself.

As he becomes more and more aware, the then begins to understand that by putting together letters, we make words.

Montessori Language – Preparation for Writing

Much of the work within an early childhood classroom is preparing a child to read and write. Moving from left to right and fine motor skills. Writing requires the brain to understand how certain letters and sounds come together to make words and the fine motor skills and coordination to hold a pencil.

A moveable alphabet is a tool within Montessori that guides a child toward writing as he visibly creates words from letters. The work is “hands-on” so a child must use his hands and his language mind to create words. Sandpaper letters and a sand tray provide a similar experience.

Related: Ways to Encourage Preschoolers with Writing

Montessori Language – Preparation for Reading

Unlike writing, where a child has control over the language he chooses to symbolize with letters, reading presents a child with something a bit more abstract. He must organize and place symbols on other people’s words. So a child first studies and then synthesizes when he reads. First Readers like Bob’s Books and Miss Rhonda’s Readers are great tools to help a beginning reader.

Montessori Language Sequence of Lessons

- Montessori Pre-Reading Series

- Montessori Pink Series

- Montessori Blue Series

- Montessori Green Series

- Montessori Grammar

How to Organize Montessori Language Materials

The language area in a Montessori classroom is extensive. Because of this, it can be difficult to find ways to organize and store everything. This section includes the complete sequence of Montessori language materials, shelving requirements, and storage solutions.